Improving community health or tackling homelessness requires a workforce. With a local hourly-labor platform it becomes easier to bring people with lived experience into those teams, each working regular hours or at times they are able.

Improving community health or tackling homelessness requires a workforce. With a local hourly-labor platform it becomes easier to bring people with lived experience into those teams, each working regular hours or at times they are able.

Community workforces evolve

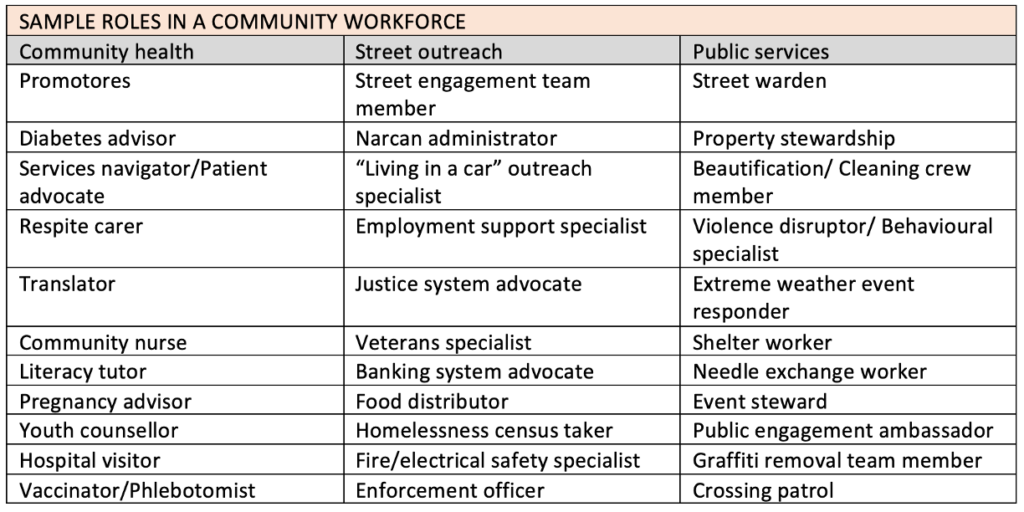

In the past, regions have recruited office-based professionals to address community needs. Now, they tend to seek a more authentic option. People with a spectrum of lived experience can be trained and supervised to engage, understand, and support clients experiencing challenges. But each of those workers could have life issues that stop them reporting for regular-hours employment, some may themselves need support through bad days. This workforce may be best employed by a range of community organizations, not government.

Workers with hard-won experience will likely be diverse in their life skills, hours of availability, aspirations, employment arrangements, levels of external certification, and distribution across the region. Each may be qualified for many roles. Training and supervision should be ongoing.

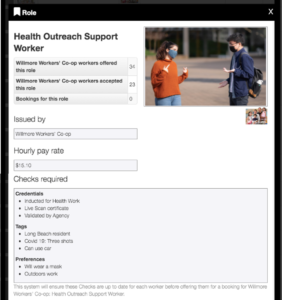

All this can be handled in a platform that allows – for example – a contact center operator to book a Nutrition Advisor for an initial visit to assess a parent struggling to keep their children healthy. As the operator immediately views options, the system has factored in rules such as full-time advisors who are available must be prioritized for bookings before on-call workers are called in, or advisors from one organization are preferred to another by the client.

All this can be handled in a platform that allows – for example – a contact center operator to book a Nutrition Advisor for an initial visit to assess a parent struggling to keep their children healthy. As the operator immediately views options, the system has factored in rules such as full-time advisors who are available must be prioritized for bookings before on-call workers are called in, or advisors from one organization are preferred to another by the client.

If Visit One is productive, 5 Monday-morning appointments might quickly be scheduled. Or a different type of worker could be tried.

This workforce does not displace professionals. Training must equip each worker to know when a client is “above their paygrade”, needing referral to a social worker or medic. But a frontline community workforce is a cost-effective way to spend time with clients who may be reluctant to receive services, and need to cautiously build trust in the support infrastructure.

Work at the core of services

Work at the core of services

A local platform can blur boundaries between service users and service providers. Some people, with severe behavioral difficulties for example, require 100% support. But others may have hours they can work, if only gently, supporting others. Baby steps into the labor market can then become a ladder.

2022 research found 94% of unhoused people have a smartphone. Around 50% are trying to do at least some work immediately. A platform adapted to multiple organizations should be able to channel a person towards employment on their own terms. That capability is enhanced if pockets of “guaranteed work” have been identified in advance. So, for instance, a city’s Parks & Rec. department might allocate $2m of their seasonal labor budget to unhoused individuals. Each qualifying person can have 10 hours of paid work, likely in a supervized trash picking squad. Hours could be taken in small chunks or as two shifts. They could start today, tomorrow, or next week.

Employment might be problematic because a person is undocumented or lacks bank details. Where organizations are willing to provide stipend-based work, the platform can accommodate this. But, whatever the circumstances, there can be a ladder. Complete a customized 10 hours of trash picking reliably and you have a track record on the local labor market platform. That might lead to subsidized employment through a workforce board program, then perhaps a place in the community workforce.

The region’s hourly labor platform takes workers out of silos. Equally open to private sector employers, it encourages transition out of the publicly-funded workforce by displaying data on individuals’ reliability, support, experience, and aims for progression to companies seeking workers.The platform can keep this seamless for the individual. Types of work can be mixed and tapered in or out. It’s all about what the client needs now, and how that best aligns with services and local labor market needs. But employment for the client can be a spine along which services sit, not a bolt-on.

An eco-system, not a monolith

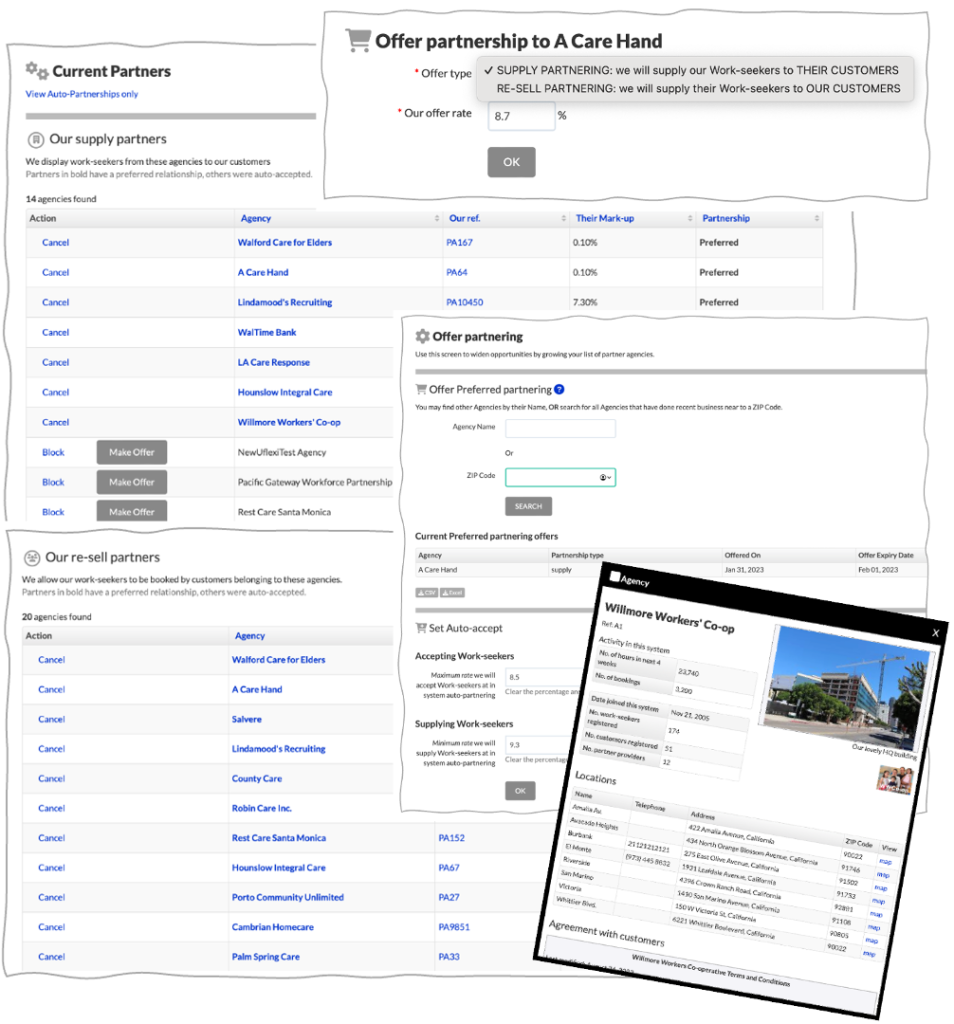

Vibrant, evolving, solutions to community challenges probably require an array of local organizations, each focused on a particular sub-region, culture, cohort of service users, or funding source. In the past, regions have tended to see this aspiration as incompatible with joined-up services. With lots of small organizations involved, service users, and workers, can become trapped in a pocket of activity, parted from the wider market.

But a regional platform incentivizes diverse organizations to partner. So, one will allow its workers to be booked by the other’s clients. Each pair agree charging rules that are applied and administered within the system on each relevant booking. With a web of partnerships around the region, worker utilization is maximized, and options for meeting each client’s needs of the moment increased.

Partnering might be made a condition of public funding for community service provision. It creates room for very niche organizations, perhaps offering workers exclusively from within one city block, or focused on support for housebound people who also need petcare. These micro-providers can get instant access to a wider market by “auto partnering” with any other organization that will accept their terms. Each organization’s rules, branding, digital badges, exclusive relationships, contractual arrangements, and terminology is enforced at every step.

Public accountability

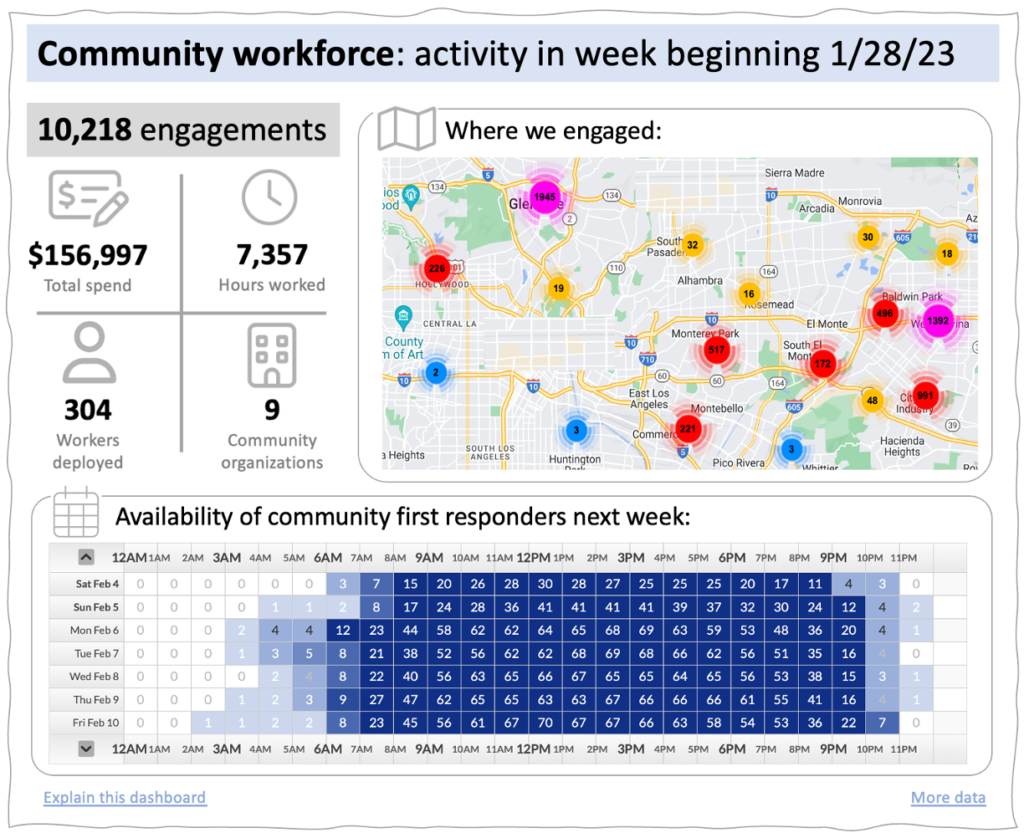

Atomized services can be ideal for clients and workers. But they are typically hard to track, threatening support from voters who provide the funding. But having a locally controlled platform underpinning diversified services creates a hose of verifiable data. If officials wish, that could be output as – to take one example – a configurable dashboard for residents:

Behind these figures is a wealth of minute-by-minute, cent-by-cent, tracking of each worker’s time on the clock against a spectrum of budget allocations. That level of data can’t be made public because it is not anonymized. But if ever outputs are queried, auditors could dive in. And a before and after census of the problems being addressed becomes easier if there’s access to reliable workers, some seeking extra hours.

To further increase cost-effectiveness, granular digital badging on the platform allows new services to be trialed and analyzed in real time. For example, social prescribing, is spreading. An initial cohort of, perhaps, 6 workers with adjoining skills, and proven reliability, could quickly be identified, then trained as prescribers, and made available around the region. How many bookings did they get? Where were they deployed? Demand for what skills decreased as social prescribers were chosen for clients? Day by day, those answers are available to planners. Ramping up a successful pilot can then be as controlled and swift as its launch.